Short Teaching Module: Connecting the French Empire

Overview

For a long time, historians tended to study colonial empires of the 19th and 20th centuries one colony at a time, or through the relationship of one colony to its metropole. Increasingly, though, historians are interested in studying global empires as interconnected systems that shaped globalization by channeling the flow (or lack thereof) of people, goods, and ideas through imperial pathways. Parsing examples of intra-imperial, inter-imperial, and trans-imperial circulations, this module suggests a few ways in which we might consider the French Empire of the 19th and 20th centuries as a circulatory system that spread limited resources across far-flung territories. Ships and shipping lanes, I propose, are ideal places to conduct this kind of analysis.

Essay

When the French Empire reached its zenith just after the First World War, it claimed sovereignty over almost seventy million colonial subjects. This was the culmination of a period that historians label as “New Imperialism,” when, from the mid-19th century until the World Wars, European empires (joined by the U.S. and Japan) unleashed the emerging technologies of the Second Industrial Revolution in a wave of conquests that propagandists often justified as the necessary costs of a “civilizing mission.” The scale of these conquests was staggering. In 1830, the percentage of the world’s land area claimed by a colonial power stood at roughly 6%. By 1913, that figure had jumped to 39%. In this explosion of imperial conquests, France was second only to Britain, claiming territories from Latin America and the Caribbean to Africa, the Levant, Asia, and Oceania.

The global scale of France’s empire presented a series of dilemmas. How could sufficient military manpower be mobilized to conquer and garrison so many places simultaneously? How, moreover, could durable connections be established between metropolitan France and imperial territories as far afield as Indochina in Southeast Asia, Madagascar in the Southern Indian Ocean, or New Caledonia in the South Pacific? Answering those questions requires that we follow circulations of people along paths that were trans-imperial (across multiple empires), inter-imperial (between empires), and intra-imperial (within an empire). Indeed, with these three terms in mind, we might envision empires as circulatory systems that maximized limited resources.

Take the question of military manpower. In the “New Imperial” wars waged by France, citizen soldiers from France’s Colonial Army (an ill-defined organization that only took on a stable administrative form around 1900) were never sufficiently numerous to operate alone. As a result, they fought alongside forces recruited from colonies and protectorates across the empire. When France conquered Madagascar, in the mid-1890s, for instance, the invading army included French citizens, but also thousands of West African, North African, and Somali soldiers and auxiliaries – not to mention an international assortment of soldiers serving in the French Foreign Legion. To explain how France seized control of Madagascar, in other words, we would have to account for this complex set of intra-imperial transfers of troops and workers.

Once in Madagascar, those troops were commanded by officers and administrators whose presence also attested to the systematic intra-imperial circulations undergirding French imperial expansion. By official regulations, military officers and administrators in the French Empire served relatively short terms in one colony – typically one to three years – before being transferred to another (a process interspersed with brief repatriations to France). The following career itinerary of a French military officer serving in the late-19th-century empire was typical of this system: France – New Caledonia – Polynesia – France – Senegal – French Sudan – France – New Caledonia – France – Madagascar – France – Tonkin – Cochinchina – France. This itinerary might appear more suited to globetrotting tourists than colonial officers, but it was the product of a French state determined to conquer and garrison its global empire with a skeleton crew.

To understand how intra-imperial transfers allowed an overstretched and undermanned empire to hold together, soldiers, officers, and administrators are only the tip of the iceberg. Historians increasingly look beyond studies of individual colonies, or the binary relationships of a single colony with the metropole, and instead research how people and ideas ricocheted across a global empire. Some of these trajectories are well studied, like the deportation of participants in the French Commune to labor camps in New Caledonia during the 1870s. Other examples, like the late-19th century migrations of thousands of contracted laborers to fill plantations and mines across the empire in the Indo-Pacific, are only now attracting sustained research.

To these examples we could add the French policy of exiling deposed sovereigns to far-off parts of the French Empire, which scattered would-be sovereigns of Vietnam to North Africa, and defeated leaders of North Africa to islands in the Indian Ocean. Occasionally, this policy backfired for French authorities. For example, when Abd el-Krim’s attempt to form an independent state in the Rif Valley of Morocco in the 1920s was crushed by French-led forces, the defeated leader was exiled to the island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean. Years later, his request to be transferred to Southern France was approved, but as the ship transporting him passed through the Suez Canal, he escaped, finding refuge in newly independent Egypt. From his outpost in Egypt, he became a powerful critic of the French Empire and even succeeded in fomenting rebellions among French colonial subjects who were passing through the Suez Canal on their way to deployment in imperial wars.

Abd el-Krim’s experience provides a reminder that intra-imperial circulations cannot be understood solely in terms of departures and arrivals. Indeed, the process of transit demands attention, too. Nearly every instance of intra-imperial circulation entailed a trans-imperial voyage in which travelers came into contact with people and places in other empires. After all, moving across the French Empire almost inevitably led voyagers to pass through other empires, especially the British Empire.

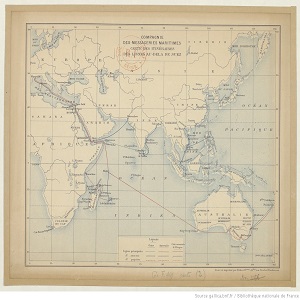

The shared highways of empire are visible in the attached route-map of the Messageries Maritimes shipping company from 1889. The Messageries was a private company that received major government subsidies and contracts for moving anyone, or anything, that the state asked it to transport, from diplomats to convicts, and from postal service to munitions. The French Navy was not large enough to carry the logistical burden of imperial expansion, so the state relied heavily on the Messageries to connect its growing array of colonies and protectorates across the Indo-Pacific. Huge amounts of traffic flowed through the company’s lines “beyond Suez,” as they were then labeled. As pictured, these routes stretched from the French port of Marseille across the Mediterranean, through the Suez Canal, to endpoints in Southern Africa, East Asia, and Oceania. Notice that the fixed layovers along these routes mostly included port-cities claimed by foreign powers. The monthlong steamship voyage from France to Indochina, for instance, usually passed through Italy, Egypt (under Ottoman jurisdiction, then British), the Suez Canal (internationally administered), Aden (once Ottoman-controlled, later British), Colombo and Singapore (both British controlled). A voyage to the French Empire, then, was trans-imperial by default.

Trans-imperial voyages both depended on, and led to, diverse forms of inter-imperial relations. Steamships of the Messageries were fueled with coal from British and Japanese depots, for instance, while the company shared facilities and pooled resources with counterparts in rival empires. Roughly half of the ship-workers who powered those steamships hailed from Asian and African ports across the routes “beyond Suez.” Many were subjects of the French Empire, but others came from the British, Chinese, Ottoman and other empires. Such workers frequently jumped from the contracted shipping lines of one empire to those of another. Among paying passengers, too, French citizens and subjects usually represented a minority onboard. The steamships that connected the French Empire in the late-19th and early-20th centuries were inter-imperial contact zones and mobile borderlands.

Inside these ships, political and business elites of European empires socialized and collaborated. During layovers, they toured each other’s ports, taking notes on imperial infrastructure and modes of governance. Meanwhile, in the lower decks, poor passengers and ship-workers traded goods and ideas. When anti-colonial politics exploded during the 1920s and 30s, many leading militants had previous experience working aboard such ships. Ho Chi Minh, for example, who would become the face of Vietnam’s struggle for independence, credited his time working as a chef’s assistant on a French steamship with preparing him for a life of anti-colonial struggle. In transit – across, between, and within empires – he claimed to have forged relationships and learned skills that would allow him to overthrow French imperial rule. Imperial circulations, then, were perhaps as critical to the rise of the French Empire as they were to its collapse.

Primary Sources

Bibliography

Jane Burbank and Frederick Cooper, Empires in World History: Power and the Politics of Difference (Princeton University Press, 2010).

Paul Butel (ed.), Un officier et la conquête coloniale. Emmanuel Ruault (1878-1896) (Bordeaux : Presses Universitaires de Bordeaux, 2007).

Nancy Delanoë, “Poussières d’empire : les soldats marocains dans le Corps expéditionnaire français en Extrême Orient (1947-1972),” in Taraud and Lorin (eds.), Nouvelle histoire des colonisations européennes, XIXe-XXe siècles (Presses Universitaires de France, 2013).

Charles Bégué Fawell, “In-between Empires: Steaming the Trans-Suez Highways of French Imperialism, 1830s-1930s,” PhD diss., (University of Chicago, 2021).

Pierre Brocheux, Ho Chi Minh: A Biography (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Credits

Charles Bégué Fawell is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of History and the College at the University of Chicago, where he defended his dissertation with distinction in 2021. He is currently preparing his book manuscript, In-between Empires: Mobility, Maritime Highways, and French Imperialism in an Age of Steam. Based on archival research in France, the U.K., and Vietnam, the manuscript tacks between the cramped quarters of steamships and the vast expanse of a maritime highway connecting France to its Indo-Pacific empire. While such steamship highways have long been understood as stable pipelines of imperial power, In-between Empires argues that they were also mobile borderlands where empire was forged, contested, and continuously remade.